I’m a fully paid-up member of the ‘marketing is a powerful force’ fan club. In 6 years in the field, I have seen how marketing creativity can be used to catapult businesses to profitability, help charities raise money and even gain a better understanding of how to structure whole organisations around their customers’ needs.

Marketing’s power extends beyond just raising income. It can do good directly, too. I have a particular soft spot for the often-overlooked area of social marketing (that’s social in the sense of benefitting society, not social media), which has made up a big part of my early career. Some of the most gratifying projects I have been involved in have sought to tackle stigma against marginalized groups, helped to remove mental barriers to accessing public services, or supported people to live more healthily.

In short, marketing people, departments and agencies serve as the primary source of creative problem-solving ability for most organisations.

That’s not to say every marketing project achieves such a big impact, or even that all those that do make a net-positive impact on the world. As a natural sceptic, I’m under no illusion of that. Like any powerful force, marketing can be used for good or for evil, but what’s undoubted is its magical ability to make something out of nothing.

Marketing: A powerful, but misunderstood force

The stats here are unequivocal. Brand reputation makes up 84% of the market value of S&P 500 businesses. The companies behind the most awarded marketing campaigns every year average +26.1% stock market growth vs the +7.5% average. Different strategies in the domain of marketing can multiply profitability by 12x (again, creativity has the largest effect). There can be no doubt that good, creative, well-executed marketing works.

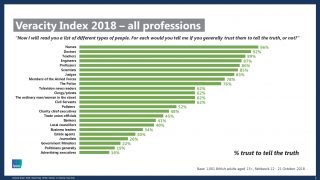

Unfortunately, out in the wider world, marketers aren’t particularly popular. In 2018, Brits ranked Advertising Executives as the least trustworthy profession behind politicians, estate agents and bankers.

Ouch.

In the news too, mentions of marketing are mostly negative. These range from the banal – such as Facebook passing off an ALL CAPS logo change as a rebrand – to the more serious, like VW Germany drawing accusations of racism or that Kendall Jenner ad for Pepsi. Then you get to the downright sinister world of political advertising, where Cambridge Analytica and accusations of Russian bots on Facebook impacting elections dominate the conversation.

Only the annual hype around the John Lewis Christmas ad brings a ray of positivity to the conversation. We could do with a bit more, surely.

So, how did this happen?

How did an industry whose sole job it is to build and promote reputations end up so distrusted? How did marketing get to the stage that it only hits the headlines when a minority get things very wrong?

Part of it might be that ads simply aren’t as good as they used to be. Since the 90s, consumers (in the UK at least) have been telling us that ads are getting worse all the time.

But that can’t be the whole story. For one, we know from the stats above that there is still plenty of creative, well-liked and effective marketing going on out there. For another, if the work is getting consistently worse, there must be a reason.

I’d argue that the root of the issue goes back a long way to, ironically, some bad PR.

A turning point in time

Back in 1957, consumer marketing was enjoying a post-war boom and agencies blossomed in the so-called golden age of creativity.

But two years before DDB launched their famous Think Small advert for Volkswagen, a journalist called Vance Packard published a book that gave marketing’s reputation a big hit.

Hidden Persuaders launched as an explicit criticism of advertising’s use of psychology and consumer research. It painted a picture of advertisers as experts in manipulation, using the latest psychological research to secretly trick consumers into buying.

The book put the idea of subliminal messaging firmly into the public domain, popularising the idea that imperceptibly short pieces of film were being cut into movies displaying messages like ‘Drink Coke’, and driving sales.

The real story

But the accusations were false. Subliminal advertising has never been proven. Unfortunately, the sensationalism stuck. The US and many others quickly banned the technique and public opinion turned against advertisers. The rest of marketing got lumped in with them.

The thing is, that sensationalism hid a kernel of truth. Marketing does influence people unconsciously. Not in the sinister or crude way that Persuaders implies, but by appealing to our internal decision-making processes. Contrary to popular belief, an abundance of research over the last 30 years has shown this decision-making process to be overwhelmingly automatic, emotional and generally hidden from even ourselves.

These days, we can evidence that one of the major ways brand advertising drives sales is not through simply telling people what’s good about a product, but through entertaining people to the point that they become unconsciously more predisposed to a follow-up sales message.

A fundamental marketing truth

We’ve sort of known this for decades. Even before this data was available, advertising titan Martin Boase summed it up beautifully:

“If you’re going to invite yourself into someone’s living room for thirty seconds, you have a duty not to bore them or insult them by shouting at them. On the other hand, if you can make them smile, or show them something interesting or enjoyable – if you’re a charming guest – then they might like you a bit better, and then they may be a little more likely to buy your product”.

Before him, Howard Luck Gossage said something not too dissimilar:

“The buying of time or space is not the taking out of a hunting license on someone else’s private preserve but is the renting of a stage on which we may perform.”

Yet despite these ideas being continuously repeated by the marketing’s very best for almost a century, our industry has shied away from them.

Paul Feldwick links this phenomenon back to Persuaders in his book, Anatomy of Humbug. He theorises that the smear journalism of Packard and others scared the marketing industry into hiding from our fundamental truths. Instead, subsequent marketers have distanced themselves from the ideas of subconscious influence, instead sticking to a party line that everything is rationally based and unthreatening.

Not long after Persuaders came out, Rosser Reeves, the man who came up with the Unique Selling Proposition, wrote in his deliberately titled book Reality in Advertising there are:

“…no hidden persuaders. Advertising works openly, in the bare and pitiless sunlight”

This is a clear rejection of Boase/Gossage-esque theory.

The psychology of playing it safe

The emerging science of how marketing works is counterintuitive. With Persuaders effectively repressing that science within marketing, the rest of the business world has moved even further away from it. In Alchemy, Rory Sutherland points to a trend of the business world becoming obsessed with economic rationality, despite psychology research showing time and again that humans simply don’t make decisions this way.

In the corporate world, it can take some real brass to forgo any product messaging and create a marketing campaign that is just a gorilla playing the drums or some moody black and white imagery of people surfing. Even though, as Cadbury and Guinness have demonstrated, that’s often the best way forward. If you do that and it doesn’t work, you’ve got to explain to your boss why you didn’t put a single explicit reason to buy in your campaign.

Guinness’s ‘Surfer’ ad by AMV BBDO is generally lauded as one of the best adverts ever and contains no product claim whatsoever.

On the contrary, if you create an ad that rationally explains how great your product is and that doesn’t work very well, it’s much easier to put the bad performance down to other factors. Logically, it seems like you did all the right things.

As behavioural science expert Richard Shotton puts it, “We’ve made marketing a business not of communication, but of telling-you-why-you-should-do-something”. That’s much narrower and ignores a whole load of value that professional communicators could add to a business (or even Government health guidance during a pandemic).

An industry divided

There has been a renewed focus in marketing on figuring out exactly how what we do works and challenging conventional wisdom in the name of making our work more effective. The likes of Boase and Gossage are being slowly proved right and researchers continue to add empirical evidence and nuance to their theories. In short, we’ve never known as much about how to make great marketing as we do now.

Unfortunately, rather than pushing the discussion around evidenced-based marketing (or just getting on with making great work), some marketers seem intent on clinging to old or unhelpful ways of thinking.

This manifests itself in a number of ways. Just one is the increasing trend of marketing that seems to be made for other marketers, rather than regular people out in the world.

For example, Burger King spent 2019 hiding a McDonald’s Big Mac behind every picture of a Whopper – to make a point about the Whopper’s relative size. They revealed the trick at the end of the year. A clever idea, but perhaps not one which will live much beyond advertising press and Twitter?

To single out BK alone would be unfair. There are plenty of examples of ads made only for awards, or even entered and winning such awards despite never even running.

There’s also a growing trend around ‘un-advertising’. Self-aware ads pretending they aren’t ads. Oasis has been doing it for a few years and has recently been joined by the likes of BrewDog, Oatly and more. I actually quite like how Oasis and Oatly have done it because they’ve added in humour and entertainment, as Boase would have wanted.

At its extreme, we’ve seen a Nova Scotia agency buy $10,000 worth of completely blank advertising as a ‘Christmas present’ to people fed up with bad advertising. The pain point is right, but the message that comes out of it is ‘we’re the problem’.

In a way, this is a bit of a rebellion from inside the industry against bad ads. That’s a good thing, but we need to be careful that we don’t undermine ourselves when we do. Stunts like this miss the point that people don’t dislike adverts, they just don’t like bad adverts.

Let’s not go back to normal

I write this as the world starts to leave COVID-19 lockdown (vaccines ahoy!). No longer in the depths of the crisis, but not out of it either. Talk throughout has been about ‘normal’. When will we go back to normal? Will we ever have our same ‘normal’ ever again? All of it assumes that our old normal was a good thing, the best we can hope for. But I think we can do better.

The turmoil of the last nine months has given us a rare opportunity to pause, reflect and then change our industry for the better, and in a big way. There are plenty of things we can and should look at here, However, I think if marketers are going to change how the world sees them, they need to start by re-examining their own self-image. Here are three ways I think we can do that.

Marketing is about influencing people. People are complicated. Which means marketing is complex too. To make the most of it, we need to talk about ‘and’ instead of ‘or’.

1. Be clearer on what we are (and what we aren’t)

One core problem marketers are facing is the way a large portion of the industry talks about itself. This vocal faction describes marketing as a logical, optimisable science. Whilst this true in part, we know that less direct, more emotional, and subconscious means of persuasion are often far more effective. As a result, we’re overvaluing what marketing can do in some ways and undervaluing it in others.

On the one hand, marketing is not a pure science. There’s no exact set formula for success and things will always be a bit messy. That might be scary if you’re a business investing hard-earned money into a campaign, but it’s the truth. What’s more, marketing can rarely make someone do something they really don’t want to do. As Leif Stromnes puts it, marketing is “a very weak force for change”.

On the other, the fact that marketing works somewhat irrationally means that we don’t have to follow a strict set of rules to see results. Our skill set and knowledge allow us to solve problems creatively and disruptively, rather than just iteratively. We should own that as a strength.

As ever, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. We know that marketing can drive real behaviour change on a large scale, but claiming that every campaign can go viral or every brand can have a world-changing brand purpose would diminish our credibility.

2. Become comfortable with contradiction

On the subject of the truth lying somewhere in the middle, we ought to become more suspicious of simple, binary answers that dominate marketing conversations. The truth is invariably more nuanced. For example:

- TV isn’t dead (but that doesn’t mean viewing habits aren’t evolving).

- Brand purpose won’t solve everything (but it’s still important when done right).

- ‘Millennials’ aren’t a valid marketing segment (Our segments should be more specific than a quarter of the world’s population).

- We shouldn’t take market research at face value (Guinness Surfer ad tanked in market research).

- Influencers won’t ‘change everything’ (they just won’t).

Marketing is about influencing people. People are complicated. Which means marketing is complex too. To make the most of it, we need to talk about ‘and’ instead of ‘or’. Or as Mark Ritson says, we need to practice ‘bothism’.

3. Be brave about breaking the ‘rules’

The flipside of being realistic about what we can’t do is making sure we make the most of what we can. The creative industry can be guilty of not being that creative in solving complex business problems. Marketers often stick too closely to their comfort zone or don’t innovate in the way they could.

Get with the culture

Marketers often talk of ‘creating culture’ but in reality, the industry is several steps behind real culture. Whilst trailblazers like Fortnite stream live concerts with Travis Scott direct into video games, marketers struggle to innovate outside of traditional ad formats. It’s time to catch up, and quick.

Output vs outcomes

Halfway through writing Not long ago, this same Martin Weigel responsible for the Vs chart above published a piece which summed this up better than I ever could, saying:

“The fact is that agencies long ago allowed themselves to be boxed in. We defined ourselves by output (ads) not outcomes (commercial impact) and left influence at the door and money (lots of it) on the table.”

Fresh perspectives

An abundance of research into creativity has revealed that great ideas need a constant stream of outside input and new ways of looking at a problem to thrive. Marketing agencies have long been the living embodiment of that theory, merging together expertise from business and social science with talent from the arts and technology to create a great result. But as time has gone on the industry has tended towards a set way of doing things. 63 years after Hidden Persuaders and all the damage it did, it might be time to shake things up a bit again, inviting in fresh points of view and debate and people who can challenge the status quo.

This of course plays into the much wider topic of diversity in the industry, which is hugely important in its own right and not one I can do full justice to here. What is clear is we need diverse backgrounds, experiences, perspectives and ideas to generate truly innovative ideas.

We’ve got a lot to do as an industry and we all need to play a role. It will take time and effort to truly improve our reputation. It won’t be easy, but building reputations is what we do best. Right?